A coral reef ecosystem is an ocean or underwater ecosystem that is characterised by reef creating corals. It is one of the most sensitive, threatened, diverse, and productive ecosystems composed of sponges, Anemones, Sea Urchins, Starfish, Crabs, Annelids, Holothurians, etc. Hence, it is known as a tropical rain forest of oceans or often mentioned as an oasis in an oceanic desert.

The gross primary productivity has been evaluated as 1500-500gC/m2/year, in contrast to 18-50gC/m2/year. They are highly efficient at recycling nutrients. Roughly 25% of the world’s fish species are found only on coral reefs. The corals are marine invertebrates.

CORAL BIOLOGY

Corals belong to the class Anthrozoa in the phylum Cnidaria. The major coral reef-creating organisms are Scleractinian corals, which are also known as ecosystem engineers. Symbiosis occurs between the coral host and zooxanthellae.

Light is an important factor for both partners, enhancing oxygen production and oxygen. Increased coral metabolism leads to increased Calcium Carbonate deposition. Due to the need for light, corals are distributed mainly in the tropical oceans, so they can receive good and ambient sunlight. They are primarily located near the equator, between 300 north and 300 south latitudes.

A few coral species are distributed in the Arctic, the Antarctic and the deep sea. Reef-creating corals are more diverse in the Pacific Ocean. The probable reason for this diversity is many species present in the Atlantic Ocean went extinct during the last ice age.

REPRODUCTION

Corals perform both sexual and asexual reproduction. Asexual reproduction or Budding is typically used as a mechanism to increase the size of coral colonies and not to produce new coral colonies.

Sexual reproduction creates free-swimming planula larvae. When these larvae settle down after swimming for days to a week, they develop a new coral colony. Some planulae are produced asexually, which results in colony formation.

Most coral species reach sexual maturity at seven to ten years of age. They are predominantly hermaphroditic; a few are dioecious (male and female organs in separate organisms).

Most corals are broadcast spawners, releasing eggs and sperms into seawater. A few are brooders, retaining fertilised eggs in the gastrovascular cavity seasonal with a single brief annual spawning event.

THE CORAL RECRUITMENT RATE

The recruitment rate of new coral colonies to the reef system varies in time and space. The higher recruitment and survival rate leads to faster reef recovery. It is high in the Great Barrier Reef and low in the Caribbean Reefs.

TYPES OF REEFS

Coral reefs occur in the two major oceanographic settings.

Shelf Reef –

- It is located on the continent shelf at a depth of less than 200 meters.

- They usually have foundations of continental crust and are located close to the mainland or islands.

- They are significantly affected by the fresh water and sediments.

- The Great Barrier Reef of Australia is an example.

Ocean Reefs –

- Reefs that rise several kilometres from the ocean floor and have limited influence from terrestrial processes and volcanic foundations fall under this classification.

The reefs are subdivided into Fringing reefs, Barrier reefs and Coral atolls. This classification is not all-inclusive and is least suitable for Shelf reefs due to their more variable nature in their morphology and ecology than oceanic reefs.

Fringing Reefs-

- Extend out from the mainland coast or island to the sea.

- The reefs of the continental coast are mostly fringing reefs, which will be narrow or broad depending on the slope.

- If the submarine slope is steep, the fringing reef will be narrow, and if it is wide, it will be gentle.

- They are usually thin and mostly comprised of veneers of Holocene coral overlying platforms of non-reef origin, and therefore, reefs will be steep with active and abundant coral growth.

- The reef flats of fringing reefs are made of scattered sand and rubble with relatively inactive coral growth.

- Passages often breach the firing reef due to the inflow of water and sediment from streams. Due to the fresh water and sediment brought by streams, these passages are located opposite the mouth and will inhabit coral growth.

- Fringing reefs are mainly well-developed in East Africa, the Red Sea, the Seychelles, the Volvanic Comoros, the sedimentary Andamans, and the Nicobar Islands.

- Windward-fringing reefs generally have straight outlines with well-matched zonation, whereas, in leeward-fringing reefs, we can notice irregular outlines and a lack of pronounced zonation.

- In some cases, especially in East Africa, we can notice a narrow repression between the reef and the land. This narrow depression is known as a boat channel. It is 100-200 m wide and up to 3m deep. It develops where sediment from the land inhibits coral growth and development.

- In India, fringing reefs are found in the Gulf of Mannar, Gulf of Kutch, Andaman and Nicobar Island.

Barrier Reef –

- Narrow, elongated structures separated from the mainland coast or island coast by a lagoon ( generally less than 3m deep).

- It can be continuous or separated by passages of varying width and depth.

- The presence of siliciclastic materials in the reef indicates the relative contributions of sediment from the land and carbonate material from corals and other marine organisms.

- Barrier reefs are not well developed in the Indian Ocean. A sizeable submerged barrier extends from India to the Srilankan coasts, the Gulf of Mannar.

- Barrier reefs will be absent around the volcanic islands.

Coral Atolls –

- Reefs that surround one or several central lagoons and most of the coral atolls are located in the Indian or Pacific oceans. Only a few are located in the Caribbean regions.

- Coral atolls have circular, elliptical, or horse-shoe shapes, and their size varies (for example, the atolls of the Maldives are around 75 km wide, while the average is about 10 km wide).

- FAROS or ATOLLONS are smaller atolls that may be present on the margin of larger atolls.

- The atolls are generally asymmetric in plan view. They are broader and better developed on the windward side because the outlets to the sea or ocean are generally located on the leeward side.

- PATCH REEFS may also be present in the lagoon. The patch reefs are small platform-like reefs. The patch reefs are located in the Ratnagiri, Malvan, and Gaveshana banks of Manglore and Kollam to Enayam on the Kerala coast.

- In atolls, the sediments are entirely Calcaerous in origin.

- In India, the Lakshadweep Islands are atoll types.

WHAT IS GUYOT ?

Islands may subdue and migrate for various reasons. Coral reefs may form on these slowly migrating or subsiding islands and fringing reefs may gradually metamorphose or change into barriers and atolls.

As the atolls continue to migrate towards higher latitudes, the change or decrease in the temperature of the water will result in a reduction of coral growth and development rates. So, the vertical reef growth can no longer keep up with the subsiding substrates, and the coral atoll drowns. This process will result in the formation of Guyots.

CORAL REEF FORMATION – THEORY

Glacial content theory-

The formation of modern coral reefs started during periods of low Pleistocene sea level, such that the shape of the current coral reef system is primarily inherited. The coral reefs that emerged above sea level during glacial lowlands have been subjected to Karst processes by the solution of Calcium carbonate.

Antecedent karst theory –

Coral reefs are thin accretions over older reefs that have been strongly modified by subaerial karst processes. Karst-eroded surfaces, with raised rims and central solution depressions, are re-colonised when rising sea levels drown atolls. Barrier reefs may be karst-induced, where the lagoon results from enhanced limestone solution compared to the seaward edge of the reef.

STRATEGIES THAT CORAL REEFS USE TO GROW AND THRIVE DURING SEA-LEVEL RISE

Coral reefs have a fascinating ability to grow vertically to keep up with sea-level rise, and changes in relative and absolute sea levels are essential factors in coral growth and development.

Three types of reef strategies are (according to their response to Holocene sea-level rise)

- Keep-up reefs -Grow vertically fast enough to keep up with the rising sea level. They can maintain shallow, frame-building communities throughout the rise in sea level.

- Catch-up reefs – start as shallow-water reefs and become more profound as the sea level rise surpasses the upward accretion rate.

- Give-up reefs – Fall behind rising sea levels and are eventually drowned.

The reef strategy for growth has some critical implications for the development of reefs and associated sedimentary deposits.

When the reef grows upward, most calcified material is retained in the reef framework. Once the reefs attain their maximum vertical extent, excess calcification is shed as detrital sediments, which become later available for reef island formation and lagoon infilling.

If anthropogenic factors and increased water temperature are not acting simultaneously, the coral reefs can generally speed up their growth with the predicted rate of sea-level rise. However, negative factors destroy reefs and make them particularly vulnerable due to their low-lying position( for example, Maldives. The low-lying position of atolls makes Maldives susceptible to sea rise).

Islands formed due to reef debris can be separated into two types:

MOTUS – long, narrow islands found mainly on the windward side of coral atolls are called Motus. The diminished capacity of currents to transport sediments across the reef controls their location. Due to this factor, they are found in linear chains that parallel the reef rim. It is characterised by ridges comprising gravel to cobble-size material at the oceanside and sand ridges at the lagoonside.

CAYS – atolls smaller than Motus usually found on the leeward side of coral atolls. The lower incidence of wave energy is responsible for the transporting and deposition of smaller-sized sediment. It consists of sand and gravel and not sand and cobbles.

Low wooded island

Continued deposition results in islands building radially toward the reef edge, and due to wave refraction, it further develops into a particular type of reef island typically found in the Great Barrier Reef called a low wooded island.

The following are the factors that control reef island morphology.

- Storms cause shoreline erosion and strip islands of fine sediment during overwashing.

- Lower magnitude storms can erode Cays.

- Energetic wave conditions and action can result in the transport of coral rubble to build eroded motus.

The net effect of small strom and clam weather events is erosive on motus. Wave action clears sediment from the islands without compensating replenishment from new coral rubble. Motus will, therefore, shrink, at least on their seaward coasts, but coral growth on the foreef constructs a reservoir of coarse sediment.

FACTORS THAT HELP IN THE FORMATION AND RESTRICTION OF REEFS

The following six factors help in the formation of reefs.

- Emergence into the air.

- Temperature.

- Depth of water.

- Sunlight.

- Salinity.

- Sedimentation.

Usually, coral reefs are found in waters bounded by 200 C surface isotherm. Reef-forming hermatypic corals can survive temperatures below this for a short period, but no reef will develop in a region where the annual mean minimum temperature is below 180 C. The optimum temperature range is between 230 C and 250 C. Some coral reefs can tolerate temperatures ranging from 300 C to 400 C.

Light is a crucial factor in coral reef development. Zooxanthellae require sufficient light to perform photosynthesis. The compensation point for most hermatypic corals seems to be the depth where light intensity has been reduced to 1-2 per cent of surface illumination.

Reef-forming corals are intolerant of salinities significantly deviating from standard seawater (32 to 35 ppt). If a large volume of fresh water is discharged, the reefs will be absent ( for example, reefs are absent in a large portion of the Atlantic coast of South America due to the freshwater discharge brought by rivers like the Amazon and Orinoco).

Sediments can have adverse effects on the corals. Even though many corals can remove a limited amount of sediment by trapping it in mucus and carrying it off by ciliary action, it can’t withstand strong sedimentation. Turbidity also reduces the amount of light necessary for photosynthesis by the zooxanthellae in the coral tissue. Some species can tolerate high sedimentation rates and are found in isolated colonies in areas with high sediments.

Wave action provides a constant source of oxygenated seawater and prevents sediments from settling on the ecology. Wave action also renews plankton, which is food for the coral colony.

Prolonged exposure to air can cause dehydration. Coral reefs limit their vertical emergence into the air to avoid dehydration. Abundant mucus secretion may prevent dehydration for a short time ( one or two hours). The mucus helps coral survive low tide. Usually, their upward growth is limited to the level of the lowest tides. On shallow spring tides, coral reef areas may, however, be exposed for short periods, up to a few hours, which does not harm them, at least in the Indo-Pacific regions.

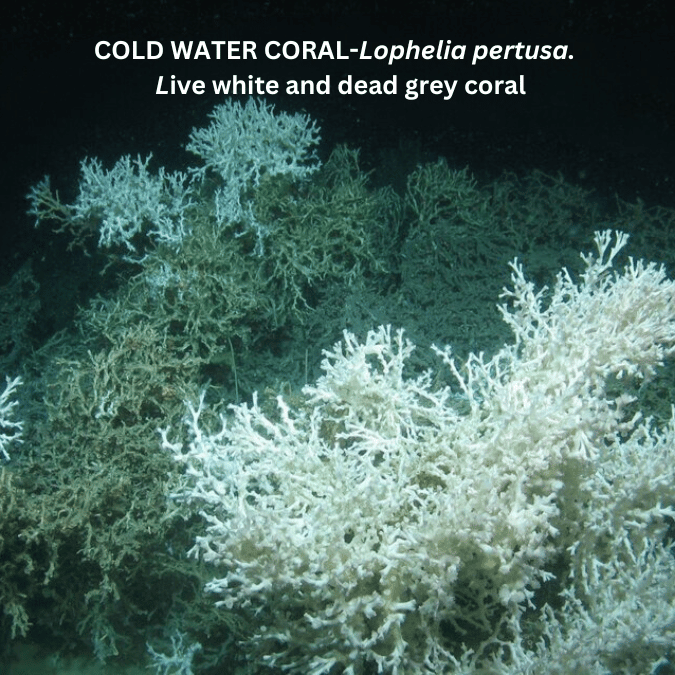

COLD-WATER CORALS

Cold water corals that lack light-dependent symbiotic algae in their tissue and grow in dark, deep waters. Since they lack symbiotic algae, they depend on the current to supply particulate and dissolved organic matter and zooplankton.

Only about six or seven framework-forming coral species make deep-sea reefs. Lophelia pertusa is the most abundant deep-sea coral in the world. The deep sea corals are adapted to feed from the water column. They capture the food that reaches down from well-lit surface waters.

Many produce calcium carbonate skeletons resembling bushes or trees to supply colonies of polyps, maximising their ability to grab food efficiently.

Cold-water coral reefs flourish along the edges and trenches of continental shelves with suitable rigid bottom substrates where cold water currents provide a regular food supply of suspended organic matter and zooplankton.

Similar conditions can be found in relatively shallow waters at higher latitudes, whereas in the tropics, they are found beneath the warm and light-flooded surface layers.

IMPORTANCE OF CORAL REEFS

- It acts as a habitat for fish, Sea Anemones, Starfish, and more, covering one-third of marine species in 0.25% of the total ocean area. For instance, Lophelia pertusa reefs in the North Atlantic nurture a habitat of around 900 species.

- Coral reefs protect beaches from erosion, storms, tsunamis, and floods and help maintain the marine ecosystem’s stability.

- It has recreation and tourism opportunities.

THREATS TO THE CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEM

CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change is the primary threat to the coral reef ecosystem. It disrupts the coral reef adaptation, acclimatisation, or dispersal mechanism. The direct effect is the increased susceptibility to coral bleaching and diseases.

According to IPCC, the projections of coral reef loss at 1.5 C was 70-90% and will lead to irreversible loss at 2 C.

Global warming and climate change increase the impact of cyclones, storms, and other natural disasters. The Keppel Bay fringing reefs are an example of a reef system affected by cyclones and floods.

OCEAN ACIDIFICATION

The decrease in the pH of ocean water over a long period is caused by carbon dioxide uptake, which shifts the carbonate system’s acid-base balance in ocean water, known as ocean acidification. The increased CO2 absorption by seawater will reduce the pH of seawater and will ultimately affect CaCO3 formation in shell-forming organisms.

The average decrease in ocean pH is estimated to be 0.1, which increases the ocean’s acidity by 26% from the Industrial Revolution era. This is already enough to create trouble for some marine species.

CORAL BLEACHING

Fluctuations in the water temperature (generally a response to a rise in local sea surface temperature of 1 – 2 C above normal (6 C in the Northern Red Sea) or unusually intense solar radiation) can create severe stress, disrupting the delicate symbiotic balance between zooxanthellae and their coral host. This will reduce tissue growth and is known as coral bleaching (loss of alga and associated colour change). When the symbionts get expelled, the consequence is hyperthermia and intense radiation.

In short, coral bleaching refers to the visibility of the aragonite skeleton of cnidarian host tissues due to the removal of zooxanthellae.

There are two types of coral bleaching.

- Mass coral bleaching event

- Seasonal coral bleaching event in deep waters

Although the severity and frequency of bleaching events vary, some species show the fastest signs of recovery (Porites, Acropora) compared to others.

1998 was the year of misfortune for the world’s coral reefs due to the EL Nino Southern Oscillation, with some areas suffering as much as 90 per cent mortality due to bleaching.

DESTRUCTIVE FISHING

Destructive fishing practices include using dynamite for blast fishing, cyanide fishing, and fishing gear like gill nets. Overfishing or uncontrolled trawling increases algal growth, which in turn decreases space for coral growth.

POLLUTION

Dumping untreated wastes and fertilisers into the ocean results in eutrophication, which ultimately destroys corals. The nutrient enrichment increases diseases and reduces coral calcification, COTS outbreaks and bleaching.

Example — The Gulf of Mexico oil spill, which resulted from the BP-operated Deepwater Horizon offshore oil rig explosion and the use of a dispersant, Corexit R, increased the negative impact on coral species and other benthic communities.

SEDIMENTATION

The sedimentation will affect the turbidity in water, reduce photosynthesis, and affect coral growth. The survival of larvae is also impacted by sedimentation, which in turn affects coral recruitment.

CORAL EATING STARFISH

The outbreak of coral-eating starfish, Acanthaster planci, affects coral growth and health. The frequency of starfish outbreaks increases with anthropogenic stressors like nutrient limitation.

The starfish feeds chiefly on scleractinian corals and occasionally on hydrocorals and octocorals.

In 1962, the starfish outbreak in the Green Island area of the Great Barrier Reef resulted in 80 per cent coral loss.

CORAL-KILLING SPONGES

Some sponges also threaten coral reefs (Terpios cf. Hoshinota). Today, coral-killing sponges significantly threaten reefs across a broad tropics region.

In this battle, sponges gain the upper hand in summer, and corals, under lower sea temperatures, will gain the upper hand in winter.

This phenomenon generally results in the death of corals over large sections of the reef, creating a knock-on effect that results in the proliferation of macroalgae and the disappearance of many reef fishes.

CORAL REEF DISEASES

Coral reef diseases are also a growing environmental crisis that threatens the function and structure of coral reefs.

White band disease affects Acropora palmata, A. cervicornis

CORAL MINING

Coral species like Platygyra, Porites, and Favia are exploited due to their dense calcium carbonate. They are used as construction material, to make jewellery, or converted into limestone.

The coral reefs of the Gulf of Mannar in India are affected by indiscriminate coral mining.

WHAT IS CORAL GARDENING?

Artificial coral transplanting as an active coral reef management option is known as coral gardening. This technique was successfully implemented in the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea.

Fragmentation or recruitment for coral growth is an initial step in coral gardening, followed by transplanting demonstrated rope-net floating coral nursery with coral fragments in plastic pins further connected to nets. Fragments were prepared from branching colonies of species like Acropora,

Genetically modified stress-tolerant corals are also used for coral gardening.

GLOBAL INITIATIVES IN CORAL REEF MANAGEMENT

- Global Coral Reef Alliance: This is a small non-profit organisation dedicated to restoring and managing coral reefs. They developed Biorock for electrical coral reef and marine ecosystem restoration and Hotspot for predicting coral bleaching from satellite sea surface temperature data.

- International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI): It is a global partnership founded in 1994 by eight governments: Australia, France, Japan, Jamaica, the Philippines, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. It was announced at the First Conference of the Parties of the Convention on Biological Diversity in December 1994 and at the high-level segment of the Intersessional Meeting of the U.N. Commission on Sustainable Development in April 1995. ICRI now counts over 100 members.

- Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network: This is a network of scientists, managers, and organisations that monitor the condition of coral reefs worldwide. It aims to provide the best available scientific information on the status and trends of coral reef ecosystems for their conservation and management. It was founded in 1994 and publishes extensive global, regional, and thematic reports on coral reef status and trends.

- The Aichi biodiversity target 10 of the convention on biological diversity aims to minimise the anthropogenic pressure on coral ecosystems and other vulnerable ecosystems impacted by climate change or ocean acidification. Target 6 and Target 11 also focus on protecting coral reef ecosystems.

CORAL ATOLLS OF LAKSHADWEEP

The islands of Lakshadweep are the northernmost atoll of the Indian Ocean. This group of islands is located between 80N and 120N and includes 36 islands, three reefs, five submerged banks and 12 atolls located in the Arabian Sea off the coast of Kerala state, India.

Lakshadweep atolls are a group of small, elliptically shaped ones that rise from the Chagos Laccadive ridge( about 150N to about 100S), supporting the Lakshadweep, Maldives, and Chagos islands.

The 200km wide and about 2600m deep nine-degree channel separates Minicoy from other islands.

This area is substantially influenced by the Indian monsoon system(both summer and winter). The summer monsoon season includes the strongest winds and is the rainy season that brings more than 60 per cent of rain. The rain generally decreases from south to north. Cyclones moving from east to west affect this area, most frequently in the post-monsoon period.

During the summer monsoon, waves from the southwest and west can reach a height of 5m, and during regular periods, the height averages around 1.4 to 1.5m.

Tides in this area are mixed diurnal-semidiurnal, with two markedly unequal high tides and low tides daily. The spring tides range 1.5m, and the neap tide range is 75cm.

Winds and currents move nearshore sediments on the western sides of the islands to the north during the winter monsoon but with a more significant effect during the more active summer monsoon.

The western rims are often submerged and expose the lagoon to monsoon currents. The western lagoons are shallow and usually covered with sediments. However, the eastern rims are typically developed as islands 2-7m high, rising from a 1 to 2 km layer of coral debris followed by an overlying limestone conglomerate and fine sand. Most of the islands in this area face the open Arabian Gulf and are submerged. The Eastern islands face the Malabar coast (coast of Kerala state, India), receiving some protection or security from the west and are open.

Corals are generally restricted to the outer reefs, with a scattering in sandy, often shallow lagoons, typically 1-5 deep.

In BITRA PAR, reefs cover most of the flats. An extensive shallow reef system has been developed in this area.

In AGATTI, coral genera Acropora and Porites were among the abundant genera.

In KILTAN, corals of genera Acropora (11 species) and Heliopora form large groups in shallows.

The shallow lagoon of KADMAT supports several species of Acropora with mushroom corals(Fungia), and about 52 per cent of the lagoon is covered with seagrass at a depth of two to five meters. In 1998, this island faced a severe coral bleaching event.

The lagoon of KAVARATI is a 2.9 km2 trough between the outer reefs and the island. This island possesses massive Porites and branched Acropora corals, especially in the northern half at 1-3m depth.

The falt reefs of MINICOY support several species of Porites and species branching species of Acropra. The eastern rim is shaped like a hockey stick. We can notice small habitats for Mangroves and their associates on this island.

MORE INFORMATION

https://www.unep.org/topics/ocean-seas-and-coasts/regional-seas-programme/coral-reefs